Building H #88: Why can't we build more houses?

To live in urban America in 2023 is to bear witness, every day, to our collective failure to build enough houses for people to live in.

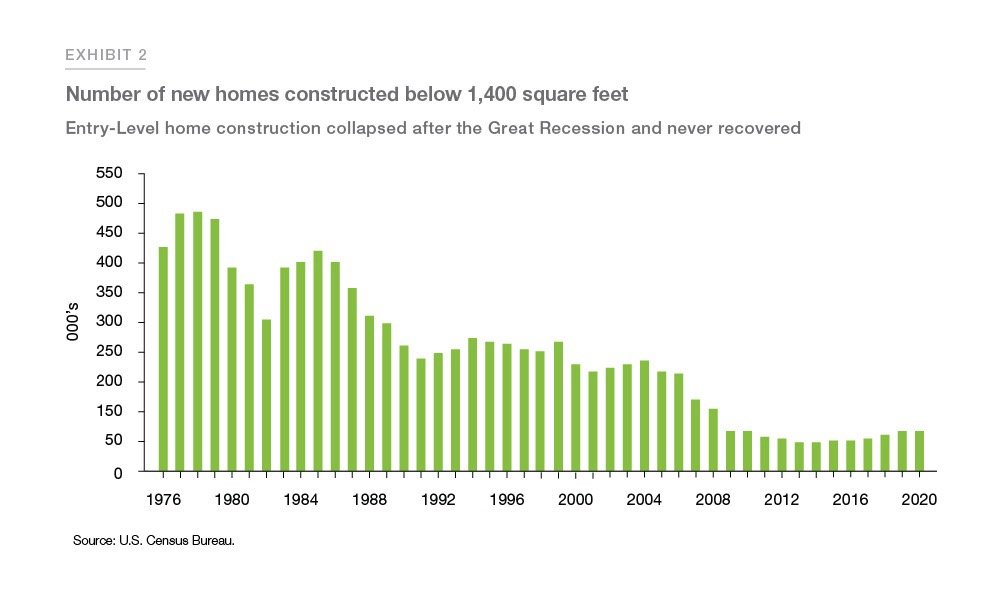

Today’s housing shortage is a crisis 50 years in the making - a history that we won’t get into here - but it means that, nationwide, the US is behind by nearly 4 million houses, according to a 2021 Freddie Mac analysis. California alone is responsible for ¼ of that amount - a million homes short. Especially grave is the lack of smaller single-family homes, so called starter homes, which have historically been an affordable on-ramp for Americans to find stable housing and perhaps generate wealth.

San Francisco, where Thomas lives, needs 82,000 homes - but just 3,000 were built last year. Princeton, N.J., where Steve lives, has been trying to boost its housing supply for years, but remains short of affordable inventory. And data out last month suggests that 2023 looks to be a loser in terms of building, especially on the West Coast.

This shortfall creates a cascade of consequences. Insufficient housing means unaffordable housing (that’s the law of supply and demand), pushing up not just the cost of buying a home, but the cost of renting, too. The average American renter now spends more than 30% of their income on rent - a threshold marking unaffordability, meaning that people have trouble paying for other necessities like food, education, transportation, or medical care. It also means people are forced into compromised housing, living far from their work, or their extended families.

The resulting stress inevitably creates other downstream impacts on physical and mental health, along the “four pathways" between housing and health: stability, quality & safety, affordability, and neighborhood. (Worth reading: this 2018 Health Affairs literature overview of the connection between housing and health. Less wonky but equally compelling: Works in Progress, an online magazine, put out an excellent piece in 2021 on how lack of housing explains pretty much every social ill, including obesity and other health issues).

This is a problem long in the making but nonetheless one that needs to be addressed with absolute urgency. Indeed, more housing should be a no-brainer across stakeholders and constituencies. Solving the housing shortage is a broadly bipartisan issue, where people across the political spectrum agree that more must be done. But that motivation gets gummed up at the local level, in the maw of outdated zoning rules and NIMBYism (perversely it’s often progressives who are most opposed to more housing, under rhetoric and rationales that defy basic economics and logic).

Per our name, Building H counts housing as one of the four key industries driving health in daily life. We believe it’s essential to build, to create more housing in communities across the country, giving people affordable opportunities to live where they want, in communities that nurture healthier lives.

So what’s to be done? Putting aside macroeconomic issues like the cost of construction, labor shortages, and interest rates, we here offer five strategies that could be pursued today to accelerate the pace of new housing construction - housing of all types, in all places, for all people.

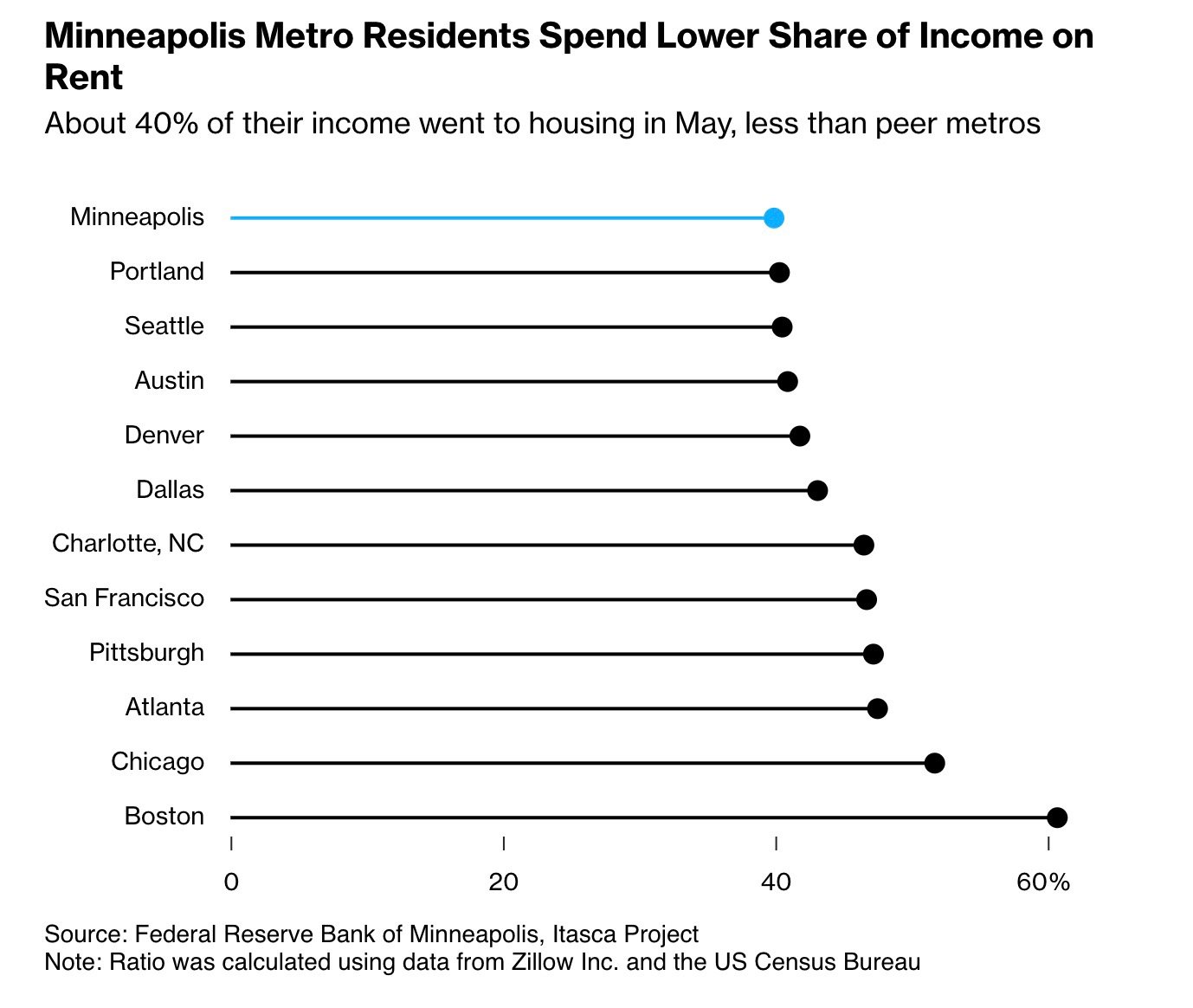

1) Slash red tape! Too many cities are handcuffed by out-of-date zoning that reflects 1950s ideals about housing and single family homes. Removing these restrictions can boost housing construction and rapidly reduce rents. Just see what’s happened in Minneapolis, which in 2018 removed single-family-home restrictions citywide, and has since seen a boom in affordable housing - and also lower inflation rates in general. In addition, cities should eliminate well-intentioned rules and fees involved in getting a house built, fees that add significant costs and delays to development, and dissuade builders from building (talking to you, San Francisco).

2) Densify! One rule that many cities should dump are per-unit parking space requirements, which means precious real estate gets turned into parking lots. That, along with more multi-story housing, can more effectively use real estate to create more dense, more lively communities. This is a very different approach for most cities, but it’s one that is gaining steam with so-called YIMBY advocates, who have organized in Austin and other cities to demand governments fundamentally change their approach to housing policy.

3) Convert! There’s been a ton of coverage this year about how all that suddenly vacant office space in major cities should be converted into housing. It’s a great idea, but not exactly the panacea many hope. But that’s not the only type of conversion that could happen. All those empty shopping malls, casualties of the declining retail sector, are also ripe for reuse. Many of these are not in downtowns but in suburban locations. Developers in Orange County, Calif., are moving ahead on several projects to convert old Sear’s properties into housing.

4) Grow! YIMBYs are right that many people want to live in cities, but can’t afford to. But plenty of folks would just as soon stay in the suburbs, thank you very much. Let them! But make sure the suburban communities foster connection, not isolation. The new suburbs won’t be “bedroom communities” - they will be places where people will want to do more than just sleep. Walkable, livable suburbs should be the goal, with a mix of single-family and multi-unit housing. MIT’s Alan Berger has advocated this approach as a wholesale new way to think about suburbs (see his manifesto in the NYTimes, or nerd out with Infinite Suburbia, a collection of essays and graphics co-edited by Berger).

5) Partner! Since housing is a health issue, it should be a concern of the healthcare industry - one the compels action and engagement, not handwringing. Building H collaborator Samir Khanna has encouraged health insurers to do the math - housing is correlated with better health - and partner with developers to invest in affordable housing (which sounds way better to us than building more and more hospitals, which seems to be the development healthcare love best). California Governor Gavin Newsom seems to get this message, as he has recently advocated for Medicaid to pay for 6 months of rent. More creative partnerships are in order.

The broad argument here is partly basic economics: We need more housing - all kinds of housing - to move more supply into the housing market. But we also need to act with urgency and enthusiasm, the same kind of verve that created a building boom in the 1950s and 1960s. But this time, 50 years later, we can build housing that is more diverse, more inclusive, more affordable, and more amenable to health, wellness, and happiness. This housing need is also an opportunity: it gives us a chance to build healthier communities, creating better infrastructure for health. And it can - it will - also help people live better lives.

Other ideas? Comments are open below.

Read the full newsletter.